WHAT ARE MANDATES?

- Andrea Consults

- Mar 4, 2022

- 4 min read

What is a mandates?

We have heard this word bantered around for some time now, and it is important for us to understand and appreciate what the application of this phrase translates to legally and politically.

Have you thought about it?

What is your conclusion?

Whaat rabbit hole has your research led you down?

The definition of a mandate is 'an official order or commission to do something, or the authority to carry out a policy, regarded as given by the electorate to a party or candidate that wins an election'.

A mandate has not received royal assent, and it has not been subject to the proper due process of first, second and third readings, parliamentary debate and human rights checks which all legislation requires in our parliaments before it officially becomes an Act.

In politics, a mandate is the authority granted by a constituency to act as its representative. Elections, especially ones with a large margin of victory, are often said to give the newly elected government or elected official an implicit mandate to put into effect certain policies.

Mandate is a political idea in two senses.

Mandate doctrine derives from the politics of responsible government on a democratic basis. It does not derive from constitutional, legal or parliamentary prescription.

A mandate is not, and should Never be a substitute for prescribed constitutional, legal or parliamentary procedures, though it may influence the workings of such procedures.

Mandate doctrine has been mainly developed by politicians in political forums rather than by philosophers or academics.

The purpose of mandate doctrine is to accord a larger role to the people than simply casting a vote at specified intervals. It is about politicians declaring the philosophies, principles, policies, plans and programs which they will support if they win office.

President Eisenhower furnished a succinct definition of what mandate is about. He entitled the first volume of his presidential memoirs, Mandate for Change, and the relevant chapter, 'Promises to Keep'.

There is considerable debate about what a mandate is. Does it apply to the entire platform (or manifesto) of a winning party only to the more important item or to matters mainly the subject of contention during a campaign? And can others, apart from winners, claim to have a mandate?

There is also considerable debate about how a mandate may be discerned-seats in a legislature, seats in which chamber of a legislature or the voting strengths which lie behind respective party strengths in parliament? And what of voting strength not translated into representation?

In the UK, mandate ideas were related, first, to the rise of campaigning and the need to tell the voters how power, if won, would be exercised. They were also important in the ascendancy of the House of Commons over the House of Lords.

In Australia, it has been a different story, especially since adoption of the 1948 method of electing Senators. As a consequence, disputes between the Houses are more likely than previously, but it is less likely that they will be resolved by recourse to simultaneous dissolutions of the Houses except with respect to the legislation on which the dissolutions are based.

The debate in Australia during and after the 1998 elections reflected the long history of discourse on mandate doctrine and embraced many of the elements which have arisen during the past two centuries of democratic responsible government

Academic analysis of mandate matters is divided. Some authors consider it is a political idea which seeks to give meaning to elections and that criticisms are based on overly literal definitions of the term. Others believe that the legitimacy of democratic politics requires that, as much as possible, commitments made on the hustings should be honoured once the election result is settled (recognising that there are circumstances where a mandate will lose its relevance or be overtaken by events), and

Critics of mandate doctrine portray it as a device for nullifying or circumventing due processes of government and legislation. The conception of mandate doctrine which they criticise is the product of rhetoric rather than more considered exposition.

J.R. Nethercote Politics and Public Administration Group,

11 May 1999

And, this is where I wish to land my comments.

According to the section 167 Public Health Act 2016 (WA) legal test, the Minister cannot made a Direction, unless the following three elements of the legal test is satisfied:

that it is an exceptional circumstance;

that the Minister has discussed this with his colleagues and they agree;

that there is a threat to public health, life and safety.

This legal test is mirrored in section 56 of the Emergency Management Act 2005 (WA).

The public interest is the basis upon which Governments and politicians often make decisions. But, these decisions need to be proportionate and reasonable.

Section 3 of the Public Health Act 2016 (WA) provides us with a proportionality test, and section 202 proves a reasonability test.

These are common tests in law, and can be objective, in that they can rely on data, facts and reports to ascertain proportionality and reasonableness.

This is the reason we have the legal tests in sections 167 and 56 respectively.

This is our proportionality and reasonability test for whether an emergency exists or not.

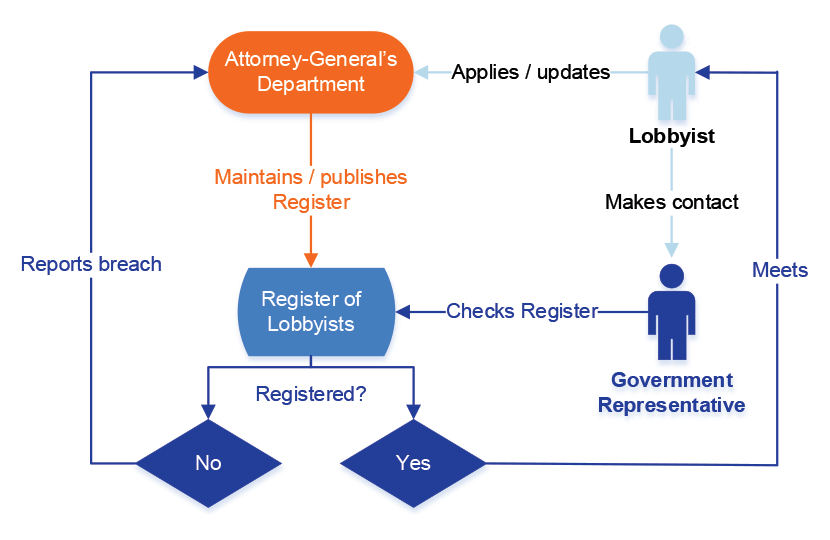

So, if you think that the current Government have not been as transparent or as forthcoming with this information as they should have been, it is up to you to LOBBY and ADVOCATE for change.

This is imperative.

It should be done strategically, with reporting, petitions, with strategies and solutions suggested and with the best interest of the community, economically, socially and in relation to welfare as much as possible.

So, how are you going to advocate for change today?

How are you going to get involved in political lobbying to keep the Government to account?

I have previously provided a lobbying resource on this matter here, which you can use to lobby the Minister for Emergency Services, the Health Minister and Premier in relation to holding them to account on, and asking them for evidence for the justification for our state of emergency.

On my count, this has not been provided once to the people of Western Australia - not once in the last two years, despite the emergency legally only lasting 14 days, and requiring a justification as to why it should deserve renewal after each 14th day lapses.

Have you ever seen this data?

What are you going to do about it?

Take back control of your country!

It's yours!

Comments